Arie Koelewyn: A sense of permanence

by Will Gorman

Arie Koelewyn of East Lansing, Michigan probably creates fewer than 20 prints per year. His knowledge, however, is creating countless waves of impact.

A retired computer programmer, Koelewyn has been operating the Paper Airplane Press out of his basement in East Lansing, Michigan for decades.

And for the past 12 years, Koelewyn has taught a Thursday evening workshop at Michigan State University; other days, professors bring their classes in to work, hands-on, in Koelewyn’s printing room at the university.

The subject? Letterpress printing. The rules? Come in and learn how to print however long he’s there.

“So far, I’ve found one student who I’d trust in a print shop by herself,” Koelewyn said.

It’s a position he had initially turned down. A residential professor at the college reached out to him and invited him to take a look at the presses available at Michigan State.

Both presses were broken and in pieces. Resurrectable, sure – but the presses each had a handful of defects and user dangers that turned him off from the job initially.

But he went on the hunt for a better press that would be efficient in a workshop scenario, and after a tumultuous trek to retrieve it, Koelewyn brought a press back to the university that’s still used frequently. He’s outfitted it with four presses and around 100 cases of type.

“I got involved because they didn’t have anything to work with. I found them the type and presses and then it dawned on me that they’re gonna need someone to show how to use them safely,” Koelewyn said. “So I very happily became more and more enmeshed in that.”

Freshly married and pursuing his Master of Science in librarianship, Koelewyn set out to find a full-time librarian job in Philadelphia. While on the search, he found himself at a part-time job at the Rosenbach Museum and Library.

At work, he was a tour guide with a lot of free time on his hands.

“When we weren’t guiding tours, which wasn’t all that often, to be honest, they let us roam around the collection at will,” Koelewyn said.

Koelewyn stumbled upon a collection of private press books in his free time at work. And as a library science master’s student, he decided putting together a collection of private press books was worth his time.

He hit a roadblock and came up with an alternative.

“I couldn’t compete with people on first editions, or even modern editions,” Koelewyn said. “Just too damn expensive. So because I’m a librarian, I could find things fairly easily, and I decided to pick the topic for my collection of paper airplanes.”

There was both ease and difficulty collecting paper airplane construction manuals. Some modern editions were easy to find, growing his collection to a respectable size. Books could be pricey, rare, obscure, but the challenge was welcome.

“I like to brag that I have the world’s largest collection of paper airplane books and materials,” Koeleywn said.

Eventually, Koelewyn self-published a small type-written book on paper airplanes. Printing 52 copies, Koelewyn tried to turn a profit by selling the first edition of the purple-covered “Paper Airplanes” book, but it was mostly a break-even venture.

“That was one of the last times I tried to sell anything related to printing,” Koelewyn said.

But he enjoyed the experience, and found out that a colleague of his wife’s had a printing press to get rid of.

Koelewyn ventured from Philadelphia to Wisconsin to pick up an 8-by-12-inch Kelsey tabletop press, his first ever.

That was 1977.

Koelewyn jumped around from Philadelphia to Ohio, Ohio to South Carolina and South Carolina to Michigan. It was there he began to seriously look for a replacement for his “crappy, crappy press.”

In the mid-90s, he finally found an 8-by-12-inch Chandler & Price (C&P). Originally, said press had been in use at a local middle school in East Lansing. While it’d seen its fair share of wear and tear in its (Koelewyn assumes) 60-70 years of operation, Koelewyn still refers to it as his main press, one that’s still in his office today.

“It still prints well enough for me,” Koelewyn said.

Over the years, he’s picked up a few other presses, including one light enough to be, if need be, regularly taken out of his workshop for demonstrations.

All of Koelewyn’s letterpress life lies strewn across his basement. On the floor, on tables – each and every horizontal space is covered in type, ink, paper, pieces, parts.

“I’m not exactly organized,” Koelewyn said. “That’s just the kind of person I am. As long as I’m the only one using the print shop, who cares where it is as long as I can find it?”

Along with that reasoning, Koelewyn manages to find humor in the matter, too.

“This is a disaster area of the first order.”

Koelewyn worked as a computer programmer for the state of Michigan for 21 years.

Within three years of retiring, due to the state frequently changing its technology, everything he had ever worked on was no longer in use by the state.

“[There was] no sense of permanence there,” Koelewyn said.

But most of Koelewyn’s printing endeavors go on to be circulated in publications and archived in libraries. Koelewyn hovers around letterpress resources – he’s been subscribed to a wide array of weekly newsletters for years, searching for any calls for submissions for any publication or museum.

Every day, he scouts the newsletters for opportunities, which have led to multiple prints for collaborative publications and annual exchanges. Throughout the exploration of his letterpress hobby, Koelewyn has printed bookmarks, folk music ephemera, poetry for local celebrations and the occasional wedding invitation among other items.

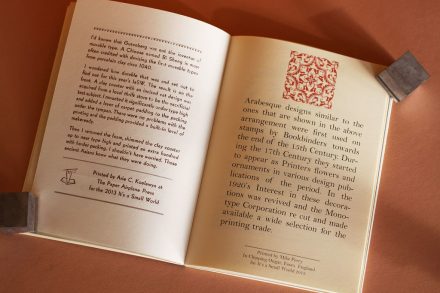

More recently, Koelewyn has been submitting prints to challenges issued by the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

After letterpress professors at the University of Oxford began devising special letterpress collections for the library, Koelewyn saw notices about challenges related to printing works by William Shakespeare and later, Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick.”

“That’s not much of a permanent legacy, but it’s way better than anything else I’ve done in my career,” Koelewyn said.

Now, he has two publications in one of the world’s oldest libraries.

“There’s some potential for permanence with this stuff. And I can’t think of any place better to put it than the Bodleian Library,” he said. “It has a really good chance of still existing in a few hundred years. So, now I’ve got two publications [there].”

Koelewyn often has helped out at Michigan State with a book arts class; however, the professor in charge of the course has recently retired. And due to the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic, Koelewyn hasn’t been able to hold his Michigan State letterpress workshop this semester.

Despite the setbacks, Koelewyn appreciates that his involvement at the university keeps him intellectually engaged.

“I get to hang around with young people who I find quite interesting. Attitudes have changed so much since I was in college,” Koelewyn said. “They’re eager, fascinated by new stuff.”

For Koelewyn, alongside the ability to help show students new technologies, he also values the community aspect of letterpress. To him, it’s practically a necessity.

“I have this print shop, and none of my children are interested in it. Somebody’s gonna inherit it and I’ve seen too many print shops go to the dump. I don’t want that to happen to my print shop,” he said.

Koelewyn keeps an eye out for students who are as invested in letterpress as he is and keeps in touch, hoping that they’ll be able to save his equipment from the junkyard.

“If that’s something I want to ensure, then what I need is a community of younger printers around me who will at least help broker the transference of my print shop into somebody else’s hands.”

They’ll be able to keep it permanent.