by Maya Fenter

Jim Horton (Ann Arbor, Michigan) has always found delight in the details. He grew up drawing and earned a Printmaking degree from Eastern Michigan University. It wasn’t until after college though, that he discovered wood engraving, and that would eventually lead him to letterpress printing.

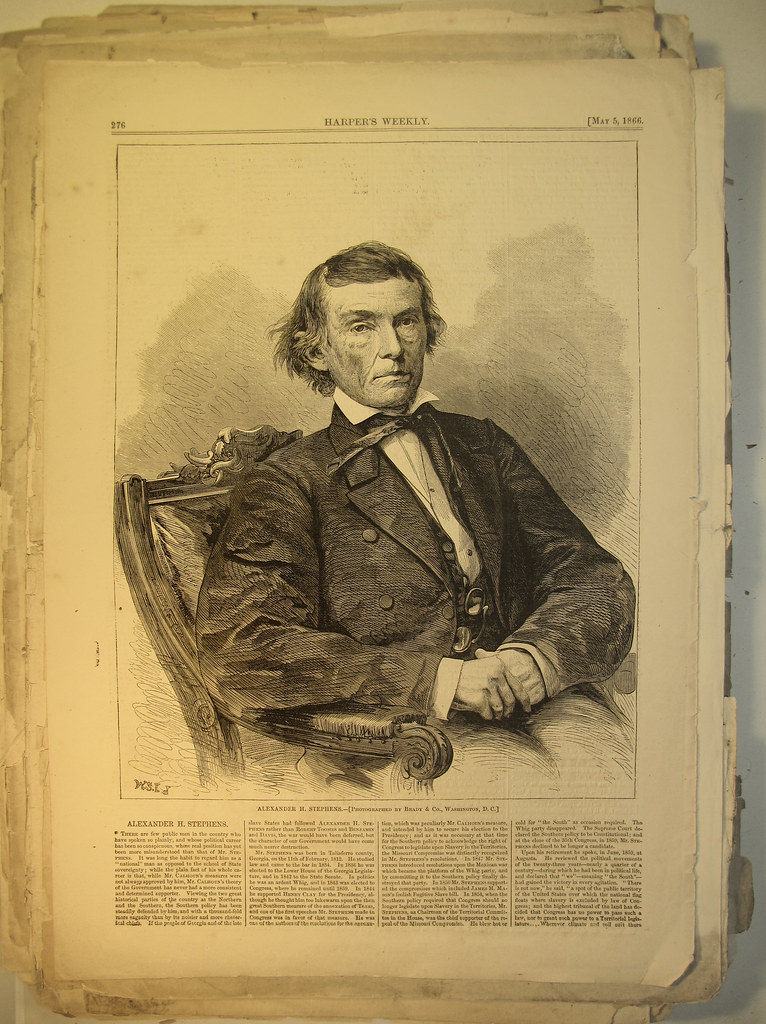

As a child, Jim Horton was always fascinated by the intricate illustrations he would see in Harper’s Weekly and Currier and Ives books. He loved to draw, so he would try to duplicate what he saw, but found that he could never quite achieve the same result using pen and paper.

Jim earned a printmaking degree from Eastern Michigan University and also took some education classes there. He went on to teach studio art and graphic design for 42 years.

Though, it wasn’t until after he graduated college that Jim discovered wood engraving. He stumbled across an article about the process, and that opened up a whole new world.

“There’s just no other process that gets the detail, and the beautiful contrasting tones and the strength that a wood engraving affords.”

Wood Engraving

Jim finally realized how they made those detailed illustrations he marveled at as a child.

“There’s just no other process that gets the detail, and the beautiful contrasting tones and the strength that a wood engraving affords,” Jim said.

Wood engraving involves working with the end grain woodblock, which has a highly-polished surface that feels almost like marble. Using sharp tools called gravers, along with chisel-like tools, you can make marks in the wood to etch out a drawing or design. Because the end grain allows for the slightest of marks to print, you can achieve very subtle tones and details.

He quickly found a love for it.

“It’s not a fast process, it’s not an immediate gratification process, it’s not an expressionistic thing where you’re making, you know, bold strokes,” Jim said. “It’s very fussy. But if you love to delve in and take your time, it’ll render whatever you want to be able to say in a drawing.”

Wood engraving has always been widely used in book illustration. Barry Moser of Pennyroyal Type is one of the prominent engravers in that area who took the art to great heights. Leonard Baskin is another well-known engraver who made prints using large-scale woodcuts.

“Alexander Stephens” by Thomas Shahan 3 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Jim studied wood engraving under David Sander, whose father ran one of the last commercial wood engraving shops in the United States and possibly the world as well. Wood engraving has always been and still is prominent in England, but for a period of time, the industry was disappearing in the United States. Jim says this was largely an effect of the modernism era, but also because there was a lack of engravers who could do the work.

During this lull, there weren’t many books being written about the craft. Sander published a book in 1978 called “Wood Engraving: An Adventure in Printmaking,” which Jim says is one of the best books on beginning wood engraving, and probably what you would find if you were researching the topic at the time.

In 2000, Simon Brett, who Jim regards as one of the finest engravers working today, wrote “Wood Engraving,” which is Jim’s go-to book when he teaches classes.

Even so, Jim believes that the best way to learn how to engrave is from a mentor who can demonstrate the process. Perhaps more importantly, these people also keep the craft alive.

Finding Community through Craft

“We’re little fish in a big pond, and are usually willing to share and be supportive as a community.”

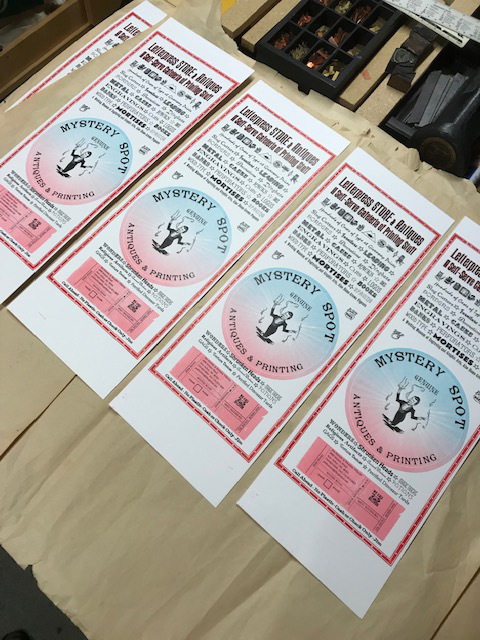

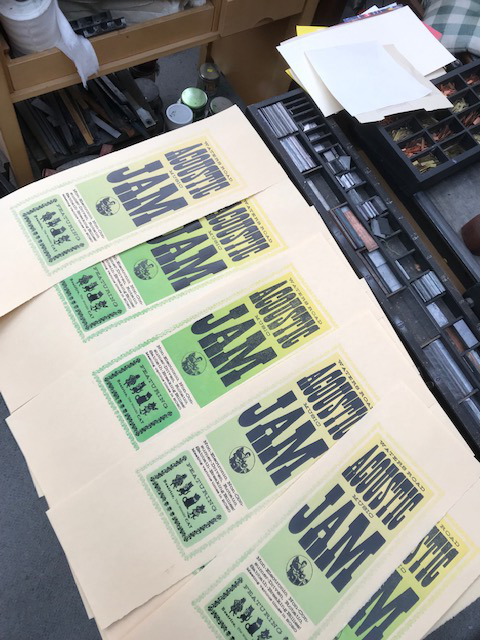

Jim’s work in wood engraving is what eventually introduced him to letterpress printing. He enjoys printing broadsides, and will add wood engraving illustrations to his projects whenever he can.

When he was first getting started with letterpress, he learned a lot from more experienced printers.

“I started finding some old guys around town that were still doing [letterpress], and they were very good about sharing and kind of pulling me into the world that existed for them,” Jim said.

From there, he discovered the Amalgamated Printers Association (APA) and went to his first wayzgoose, where he was excited by auctions for presses and type, and printers exchanging their work. He has found that printers are always willing to share their ideas and help one another. Whenever he goes to events, he always feels at home.

“We’re little fish in a big pond, and are usually willing to share and be supportive as a community,” Jim said.

Jim has been a big part of building a community of engravers as well. In 1994, Jim founded the Wood Engravers’ Network (WEN), an organization that “fosters education and creates a resource for wood engravers and the practice of wood engraving.” The organization holds print exchanges and an annual summer workshop, and also publishes a biannual journal called “Block & Burin.”

Since it began, WEN has grown to over 150 members from all over the world.

Printing Meets the Modern Day

While Jim admits that modern-day technology has great capabilities, and he probably couldn’t live without it, there’s still something that printing offers that technology lacks.

“I think that [technology] doesn’t quite satisfy some of the need for hands-on experiences,” Jim said. “And I think especially the art students that I deal with now, they’re hungry for getting away from the computer and doing things by hand and discovering things by hand.”

Throughout Jim’s printing career, he’s watched the older people he has worked with age out of the process. But this unique sense of accomplishment and creativity has inspired a new young generation of printers that he has seen emerge. At printing festivals, he’s happy to see young people making broadsides and running their own presses. It gives him confidence that the practice will continue to live on.

“I think, you know, you have to be a person that just likes the smell of ink and loves the industriousness of printing,” Jim said. “We’re very lucky that there is enough letterpress stuff still kicking around that we can keep it going.”

Jim’s Current Endeavors

Today, Jim does a little bit of everything.

He has retired from teaching, and sometimes he’ll pick up different printing jobs making invitations or broadsides for clients if he wants to make something and earn some extra cash. He holds an open studio in the Book Arts Studio at the University of Michigan, where he teaches art students the letterpress process and how to use the presses. He is also helping to set up an engraving shop in the Hamilton Wood Type Museum in Wisconsin.

For his own personal work, he pursues whatever comes around that interests him. Recently, the father of a curator at the University of Michigan found a large printing plate that was used to print kites. So they started making kites.

Printing and engraving are still as rewarding now as when he was starting out.

“Whenever I can challenge myself with any kind of a project, just delving into the design, being able to see it come to reality and actually put sweat and labor into it and seeing it come off the press, it gives life character,” Jim said.