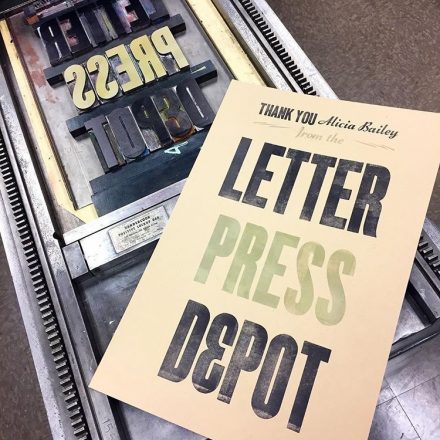

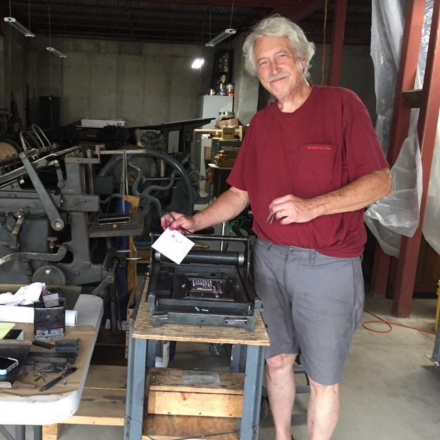

Tom Parson is a letterpress printer and poet from Denver, CO, who has always found the greatest inspiration at the center of form and function. He’s currently in the process of converting a historic 1915 train depot into the Letterpress Depot: a living museum and nonprofit of letterpress printing, typography, design, poetry, and art.

“You are tooling the language, feeling it, preserving it.”

Tom is quick to laugh, especially at his own gregariousness. “I’ll talk and talk if you let me,” he warns. “One of the hazards of printing is that you spend hours by yourself. At some point someone else walks in and you’re like, oh I can talk!” For Tom, the path to printing was through poetry. He got involved in editing the school literary magazine in high school, and by grad school was the co-founder and -editor of Consumption, a quarterly poetry magazine. He attended the University of Washington, and it was through Seattle’s vibrant poetry scene that Tom realized small press publishing was where the interesting—cool and political—stuff was happening.

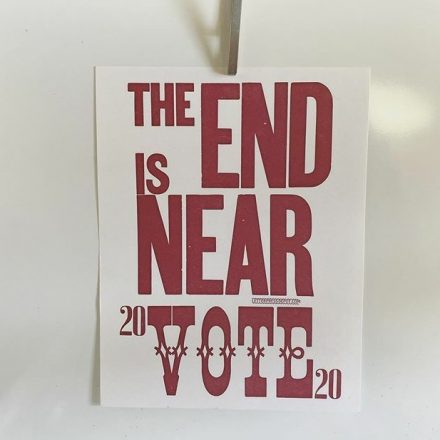

The Vietnam War loomed over Tom’s college years in the 60s. He avoided the draft by going to grad school. “I’m not someone who’s going to shoot other people; I’m just not that person.” Tom became acutely aware of the Civil Rights Movement and the politics of the Vietnam War during this time, and has been politically involved since.

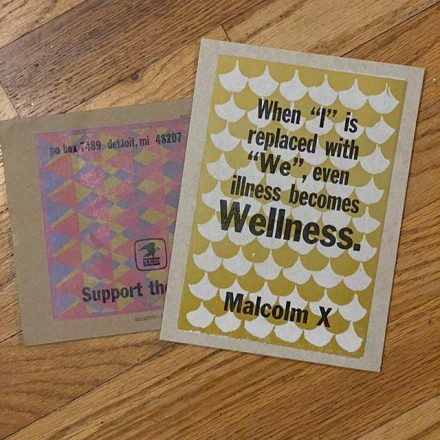

His politics and experiences indelibly shaped his poetic practice. Vital art engages with a social movement, and separating art from culture divests it of meaning. Tom puts it succinctly: “You can’t go after beauty without putting it in context.”Concrete factors like audience and intention drive Tom’s poetics far more than image and aesthetics ever could.

“A poem is not an emotion—it’s a thing. It’s the language.” As Tom describes his process, I can’t help but notice how his words ring true for letterpress as well. “You are tooling the language, feeling it, preserving it.”

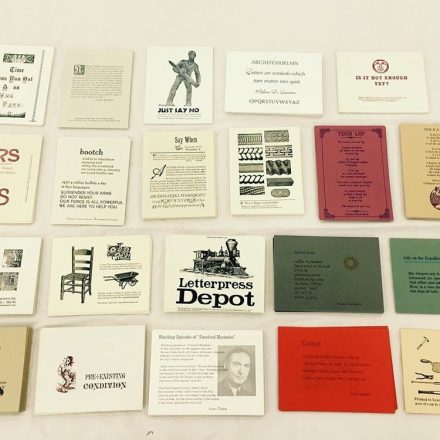

In 1970, Consumption published an anthology, The Whites of Their Eyes: a hundred pages of revolutionary poems by up-and-coming voices, a thousand copies made using offset printing. “When you’re out on the protest,” explained Tom, “you need to have a pocket full of poems with you.” The Whites of Their Eyes sold out immediately. In the late 70s, Tom organized small press book fairs, open mic nights, free coffee shop newsletters that he’d spot in strangers’ hands on the bus later. Tom began to consider the idea that he could do this—printing, making—himself.

“This is what I’ve learned from being a printer: perfection,” Tom shakes his head, “is not the right word.”

Tom purchased his first press after he and his wife Patti moved to Denver for her job in 1983. The poetry scene there was fragmented and insular, so Tom expanded beyond publishing to job printing. He hasn’t looked back since.

“This is what I’ve learned from being a printer: perfection,” Tom shakes his head, “is not the right word.”

Letterpress allows you an enormous kind of personal control; you pick the font, the spacing, the position, the paper, the ink color. Every step of the process includes infinite adjustments. The tiniest tap of ink while color mixing dramatically alters a piece’s transparency, value, and hue. Letterpress printing is all about pressure, and small changes in paper weight or spacing alter what actually rolls onto the page.

Tom even owns quarter-point (read: very thin) spacing to shift the distance between letters, but he admits the difference they make is often negligible to the client. If you can fiddle for days or weeks or months, how do you know when to stop?

“Where is the perfect?” Tom counters. “What is perfect? It’s only in the context.” One of the most important lessons a printer can learn is the difference between perfect and good enough. Tom thinks back to the very first letterpress workshop he took with Tree Swenson at Copper Canyon Press, in 1981. For him, good enough meant sitting immobilized for two days, and then launching into action (his bolt of inspiration? The typeface Centaur.) For Jim Bodeen of Blue Begonia Press, good enough meant making every wrong choice the first time. “Make a mess of it,” Tom advises now, a lesson he learned from Tree. “Go ahead and get inky, get it out of your system.”

“Once in a while someone gets the bug, just gets bit by it, and once that happens you don’t ever look back.”

Stalwart and innovative, the letterpress community has revived their craft from the brink of obscurity. Tom still remembers the industry’s initial collapse, around the time he started printing. “All the old guys are gone.” He chuckles, “Now I’m an old guy.” Wayzgoose, an annual conference hosted by the Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum, has become the mecca where printers of all ages breath life back into a dying art through talks and workshops. Tom’s continuously in awe of the inventive techniques he learns from the new generation: Brad Vetter, the Itinerant Printer, Jason Wedekind of Genghis Kern. When Jason approached Tom to help him with a client’s request for letterpress work, Tom had no idea Jason would one day open his own shop or sit on the Board of the Letterpress Depot, years later. “Once in a while someone gets the bug, just gets bit by it, and once that happens you don’t ever look back.”

Tom muses that letterpress’s practical and authentic qualities keep bringing young designers to such an old process. I can’t help but consider a sense of duty as well, to the machines and tools and techniques that would otherwise be lost to time or the scrapyard. Tom could never imagine putting a press behind glass. After a trip to the library discard sale where he purchased their entire letterpress collection for fifty cents a book, Tom is all too aware of what fate befalls the things we don’t use.

“Use it, break it, see what happens.”

“Hands-on stuff, to me is, a way to preserve it,” says Tom, who relishes the pressures from the availability—or lack thereof—of equipment. After all, the damage from floral stationary on his most-popular wedding typeface led him to home-brew his own photopolymer plates (a process that uses photosensitive sheets to form whole blocks of text); his salvaged monotype caster (a machine that makes letterforms) forced him to improvise new parts. “Use it, break it, see what happens,” encourages Tom. “One of us is going to have to solve that problem after it’s broken. You preserve it by using it up.”

That’s Tom’s hope for the Letterpress Depot: to teach workshops and give kids access to actual printing and publishing, to continue the archive through use. So far, the nonprofit has been operating out of multiple houses and the picnic table behind Tom’s double garage, which already bulges to capacity with letterpress equipment. Tom has put aside his own publishing efforts to convert the old Englewood train depot into a functional workshop, but after five years the building still lacks plumbing and heating. The dream sits limbo while the pandemic rages on but nonetheless persists with its mission to make letterpress a living resource available to the community.

“I need it in my life, I need letterpress because that’s how I understand the world.”

After two WIFI glitches and an improvised tour of Tom’s home library, our conversation approaches its end. Throughout the call, Tom has been quick to take a stance on the useful side of letterpress—what’s readable? What’s feasible? Now, he speaks of something deeper than use: need. “I need it in my life, I need letterpress because that’s how I understand the world: by trying to describe it and catch something in language that I want to go back to and read again.” If Tom feels like he stands against the inevitable pull of time, he doesn’t show it. “That doesn’t go away, even if no one ever reads it.”

Photos courtesy of the Letterpress Depot’s Instagram

Interviewed & Written by Delaney Heisterkamp